- Home

- Jack Gantos

Hole in My Life Page 3

Hole in My Life Read online

Page 3

Wouldn’t we all.

As I watched the prisoners being marched away I knew there was nothing we had in common. I wasn’t angry. I didn’t use drugs. I didn’t steal. I wasn’t a rapist. But something was wrong. I felt adrift inside, as if I had a compulsion not to be myself. I especially had that feeling when I read books. I seemed to become the main character, as if I had abandoned myself and allowed some other person to step right in and take me over. It was a great ride becoming a fictional character for a day or a week, but when the temporary visitor left I felt as empty as a bottle, and when I regained my own voice it was always strangely scarred from the experience, as though something in me had been torn open and then healed over. But that didn’t mean I’d end up in prison.

My friend Glen Martin’s dad was a sales rep for Van Heusen shirts. He sold them to stores throughout south Florida. His garage was filled with shelves stacked with samples, and after each new season Glen’s dad let him sell the samples to his friends. I was a good customer.

One afternoon I was in his garage sorting through new styles when he asked, “You ever smoke weed?”

“Ahh, no,” I replied, sounding very uncool to myself.

“Want to try some?” he asked.

“Not now,” I said. “I have to go to work.”

“Tonight?” he asked. “Come over to my new friend James’s apartment in the Lauderhill Lakes complex. Apartment 311. We’re having a weed party there.”

“Okay,” I said. “Yeah.” I was trying to sound enthusiastic, but it wasn’t working. I bought a shirt and left.

All through my shift at the grocery store I was absentminded. I had read lots of books where people smoked weed. Some seemed to really enjoy it and got happy and hungry and silly and had deep insights into themselves and the world. I had a sneaky suspicion I was going to be the other kind of smoker—the kind I had also read about who go off the deep end and let life drift way out of control, and become dependent on dope and other users to help them out, and are abused and broken down and the only deep insight they gain from the experience is that they have totally ruined their lives—and I’d end up like that girl from Go Ask Alice who went nuts on LSD and was locked in a closet after she imagined a million bugs were on her skin and to kill them she clawed off all her flesh and nearly bled to death.

By the time I finished restocking the entire canned vegetable section at work I was convinced I would be a vegetable if I smoked. Yet I went to the apartment. Why? For the same deadhead reason people climb mountains—it was there and I wanted to try it. Plus, there was the slim possibility it would make me a better writer. I got that impression from reading William Burroughs.

I knocked on the door. James answered. He was at least ten years older than the rest of us.

“Come in,” he whispered, and as I entered the room I turned and saw him peek out the doorway as if I might have been followed by the police. He was so paranoid he scared me.

Inside, the apartment was filled with smoke that smelled like an acrid palmetto brushfire. I coughed. On the living room floor Glen and four other guys were sitting cross-legged around a tall brass-and-glass hookah. Jefferson Airplane was on the stereo. Glen grinned up at me.

“We’re trying to get high but it’s not working,” he said, disappointed. “We’re just down to stems and seeds. Want a toke?”

He gave me the spitty plastic end of the hookah hose. I drew in some smoke and instantly hacked it out of my lungs.

“I know what you mean,” he remarked. “We even filled the hookah with wine but it can’t take the burn out of this stuff.”

I nodded my head in agreement as I gritted my teeth from trying to suppress more coughing. After it was determined the stems and seeds were a bust, I spent the rest of my time wondering just how long I had to hang around before politely leaving. I drank two beers, then said so long to Glen and James and the other guys I never met. They had stared at the floor the entire evening as if it were interesting. It just looked filthy to me.

All the way to my car I expected cops to grab me by the shoulder just as they had when I was exchanging the hot stereo. I didn’t want to be busted and thrown in jail so that someday I could tell my sad tale to others, just as the prisoners had told their woeful tales to me.

When I made it home I closed and double locked my door and pulled the curtains.

“I don’t have to do that again,” I said to myself. But I must not have been listening.

I lived in the King’s Court for the whole school year. Davy baked and left cookies on my bed, and she always monitored my health and mothered me with homemade soup when I was sick. Her motel catered to a patchwork of local folks who were down on their luck. Florida was still pretty segregated, so the cultural mix was unique and mostly peaceful—blacks, whites, Hispanics, and some Seminoles. Every now and again the Seminoles would get drunk and claim that Florida was their territory and everyone else had better pack up and move out. Parents made sure the kids were inside and the doors locked during these tirades. Davy let them shout and parade around in their native costume as they called on the spirit of Chief Osceola to help them regain their homeland. She only pulled out Ole Betsy and called them a bunch of “alligator wrestlers” when they walked onto Broward Boulevard to scare cars, or when they busted up furniture and threw bottles of Ripple and Boone’s Farm through the jalousie windows. She never called the cops on anyone. Her frontier policy was to work it out among ourselves. Besides, she felt for the Seminoles.

“They got every right to be pissed,” she said. “It wasn’t so long ago the government paid two hundred dollars bounty for every Indian killed by settlers.”

When I told my school friends where I lived they thought I was joking. For most of them I might as well have been living in the Black Hole of Calcutta. When my drinking buddy, Will, came to visit, he was always nervous his new Camaro would get broken into or stolen. And when any of the motel kids knocked on my door for a treat (I always kept bags of candy from the store in my room), my friends reeled back in horror as if the kids had lice, ringworm, or rabies. But after meeting my neighbors they’d relax and realize that people on the other side of the tracks were warm-blooded, could tell good stories, and were as curious about white high school kids as we were about them. I named my room the “Bad Attitude Clearing House.”

Things were not going well for my dad’s business. The family had moved from Puerto Rico to St. Croix in the Virgin Islands with the hope that my dad could start a small construction company and make big money. He started the company, but there was not much money and my mom was worried. I had stopped asking for a monthly allowance. I just wanted to be one less thing to fret about. That was my goal. My letters home were lame, but they did not add to the general gloom and doom around the house. Even when I changed my mind and decided not to go to college, it didn’t bother them.

At first I was going to go. I had taken all the tests that counted—the SAT and the Florida Placement Exam in order to determine state college eligibility. There was only one kid out of our 700-student graduating class who was going to Harvard, and that was not me.

After I was accepted to the University of Florida in Gainesville, the only school I applied to, I was required to attend an interview with the admissions office. Before I went up to Gainesville I looked over the course offerings. The school was strong in literature but just seemed so-so in creative writing. That bothered me, but not too much because I was accustomed to not getting everything I wanted.

On a Wednesday I took off work time, packed a bag, and drove up the turnpike to I-75. I had changed the oil in my car, and had the brake pads replaced and the engine tuned. The car drove beautifully. I loved my car. I felt even more comfortable in it than I did in my room. They were about the same size and had about the same amount of furniture and closet space.

I arrived on campus early. I drove around the dorms, the library, the classroom buildings, and the administration offices. It was 1971 and the campus was dozing. Ac

ross the country students were rioting over civil rights, Vietnam, social justice, and government cover-ups involving tapping phones and secret wars. While in high school I accepted that I was living in a void, but now that I was heading for college I needed some fresh air and fresh thinking. Granted, my mind was pretty blank to begin with, and I wasn’t exactly sure what I wanted or what I needed, but I was totally certain what I didn’t want. And I didn’t want the University of Florida. It looked just like a big, sprawling high school. It was everything I feared, and it gave me the creeps. As I drove around I came to the conclusion that I wasn’t going to go. I wasn’t going to just bump along to grade thirteen and not go to a real school where I’d be roughed up and challenged. By the time I parked my car and entered the admissions officer’s cubby, I was determined. The lady who met with me was very nice. She shook my hand and welcomed me to the college. She gave me a little booster bag full of university items: a mini orange football with a Gator logo, a Gator car decal, a Gator hat, a Gator hand towel, a Gator mug, and a rubber Gator for the top of my car antenna.

I thanked her for the items and set them down by my feet. I was trying to come up with a way to tell her why I decided against attending the school. I suddenly wanted to blame it all on the Gator mascot, but knew I needed more than that, and more than just a gut feeling that the place was all wrong for me. Then she sealed the deal while pointing out a few freshman rules.

“ … and you have to dorm on campus for the first two years, and during that time you cannot have a car.”

I stared at her. I debated silently if I should tell her I loved my car—needed my car—and that I had been living on my own long enough to never want a roommate. But I kept my thoughts to myself. I smiled. We chitchatted a bit and I left, and on the way home I felt a huge weight lift from my shoulders. All the way down to my toes I knew I had made the right decision. But I didn’t know entirely why. I guessed I would find out later. It was a good guess.

4 / pair of jacks

Like every guy, I had read On the Road by Kerouac and wanted to cut loose and carom from coast to coast as he did without thinking of money or trouble or anything but the great freedom that awaited me like a ship heading to sea. I was looking for a change. I wanted to see something beyond high school and the King’s Court and a grocery-store aisle lined with canned vegetables. And I was especially itchy to feel new things, to shed my skin and grow. I couldn’t explain myself to anyone because I was only full of excited urges and notions and desires, kind of like the Hulk before he transforms. Plus, I had a strong sense that I needed to snap off my past in order to have a future. All year I had worked hard to keep myself together. I held my job, managed my own money, kept passing grades, and stayed out of deep trouble. But now my accomplishments just seemed like survival routines, and I wanted to move on to more romantic turf and find out who I was and what might happen to me when the rubber met the road. And, of course, I wanted to write. I figured if I crisscrossed Florida from coast to coast as if I were tying up the laces on a high-top sneaker I would eventually stumble on something juicy to write about. I was full of hope. I had been reading constantly. I kept up my daily journal-writing routine, logging my favorite quotes and building my vocabulary. And now it was time for me to stop being a chippy high-school writer and to challenge myself.

So I began to shut down the “Bad Attitude Clearing House.” I gave away all my thrift-shop furnishings to whoever would take them. I gave my suit and jacket and striped shirts and club ties and wing tips to a young guy who was looking for work. I kept my T-shirts and jeans and sneakers. I rounded up the little kids and passed out all my candy stash, which they gleefully devoured. They didn’t save one piece for later. And as I watched them prance and dance around the parking lot like sugared-up puppets, I told myself to stop rationing pleasure as if it were a paycheck. It was time to cut loose and have fun, and not worry about tomorrow. I wanted my candy, too.

Reading On the Road, I felt more like Sal Paradise than Dean Moriarty. Sal was in love with everything and everybody. His eyes were as wide open as his heart. He recorded what he saw and what he felt in equal amounts, as if he were balancing the great scales of observation and reflection. But Dean confused me. He just wanted to consume everything. He had to keep moving like a shark, and in the end he was a tragic ghost of a person instead of a stream of milky way jazz under open highways. I wanted to move like Dean, but I wanted Sal’s heart and soul.

Unlike Sal and Dean, I didn’t have years to string out a trip. I had just over two weeks for a mini-On the Road adventure. I knew I was going to join my family in St. Croix. But first, I figured I’d drive up to Jacksonville, see Stephen Crane’s house, then work my way down the state to Key West and Hemingway’s home, and finally drive back to Miami to ship the car. That was all the structure I wanted. As Kerouac wrote, “I was a young writer and I wanted to take off. Somewhere along the line I knew there’d be girls, visions, everything; somewhere along the line the pearl would be handed to me.”

I wanted that pearl.

I had spoken with my dad and told him I was putting off college and instead would help with his new company. I wasn’t any good at construction, but I could drive the truck to pick up the crews and deliver supplies and work odd tasks in between. I told him I’d be home in a few weeks. He said he was counting on me, and it felt good to be needed by him. We could spend some time together after such a long break, and I could save money for a college that was a better fit for me. I called a shipping company and made a date to ferry my car to St. Croix out of Port Everglades. I booked an air ticket for myself and thought that helping my father, saving a few bucks, and writing on my own was all the purpose I needed.

Then, out of the blue, something happened that I hadn’t planned on. My friend Tim Scanlon called. He wanted to visit. He graduated a year ahead of me and had been going to Florida State to study medicine on a full scholarship. He was a smart guy and I knew him only because we had worked together at the grocery store. I didn’t know any of his other friends and he didn’t know mine. The only reason he wanted to stay with me is he didn’t want his parents to know he was in town. He wanted to have some fun before he settled in with them for the summer. I told him he could hide out at my place for a few days, but then I was leaving. That was good enough for him.

I picked Tim up at the train station. He had changed in the last year. His hair was down to his shoulders. He wore a pair of ripped-up jeans and a Hendrix T-shirt. He looked like he hadn’t slept in a week, and by the time he got to my car he had already lit a joint.

“Want some?” he asked.

I hesitated and started the engine.

“I’m in pre-med,” he said. “It can’t hurt you.”

I took a puff, then another. After a few minutes I fell silent and all my thoughts seemed big, very big, so endlessly BIG I couldn’t get out of them. My brain hummed along as one thought segued into another. The concentration was incredible. If I had been reading a book, each page would have been the size of a Kansas wheat field. The space inside my mind seemed endless.

After a while he tapped me on the shoulder. “Good stuff,” he remarked.

I forgot I was driving. “Did I run any lights?” I asked in a panic.

He grinned. “I don’t know,” he replied, and shrugged. “I wasn’t paying attention.”

I had already quit work, so we just lounged around my room for a few days. We were so high we hardly went out. The weed dazed us until we got hungry enough to drift down the street to a pizza parlor, where we’d order two-for-one large specials and burn sheets of skin off our upper palates on the first bite. Then, with food in our bellies, we’d straighten up a bit and go back to the room and smoke a joint and settle down to talk up a storm. He liked my books.

“I guess you read a lot,” he said, digging through the open boxes. “You ever read Hallucinogens & Shamanism by Harner?”

“Never heard of it,” I replied.

“He’s incredible,” he

said. “He believes that hallucinogens are the way we get in touch with our animal past. That in our DNA is stored genetic memories of when we were an evolving species and when you take the stuff the Indians of Brazil take you’ll access your genetic library all the way back to cellular experience.”

That seemed impressive to me. He talked about a lot of books I’d never heard of. Scientific books on animal communication. Studies on dancing bees by Karl von Frisch. Reports on enzyme exchange communication between termites. And a book called Insect Societies by Edmund O. Wilson that linked human behavior to animals from apes to insects.

“All behavior is chemical,” he said, getting so excited he stood up and paced the room and beat his fists against his thighs. I pegged him as my Dean Moriarty and was happy he showed up with his wild genetic ideas. “Your memory is just chemistry. Your motivations. Your everything. You have to read the stuff I read,” he insisted. He wrote out a frenzied list, and with each title he let out a hiss of excitement, pushed the hair out of his eyes, and pronounced each book better than the last. “This stuff on bio-communication is the future,” he said. “It will take you back to the why of everything. Remember when you were a little kid and kept asking why and your parents gave you some half-baked answers? Well, these books get down to the root of the why. If you understand this stuff you will understand everything—religion, politics, psychology, art—the history of all human desire is entirely in our chemistry.”

Jack Adrift

Jack Adrift Jack's New Power

Jack's New Power Jack on the Tracks

Jack on the Tracks I Am Not Joey Pigza

I Am Not Joey Pigza The Bloody Souvenir

The Bloody Souvenir Joey Pigza Loses Control

Joey Pigza Loses Control Heads or Tails

Heads or Tails Hole in My Life

Hole in My Life What Would Joey Do?

What Would Joey Do? The Trouble in Me

The Trouble in Me Joey Pigza Swallowed the Key

Joey Pigza Swallowed the Key From Norvelt to Nowhere (Norvelt Series)

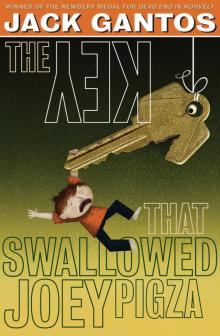

From Norvelt to Nowhere (Norvelt Series) The Key That Swallowed Joey Pigza

The Key That Swallowed Joey Pigza Jack's Black Book

Jack's Black Book Dead End in Norvelt

Dead End in Norvelt