- Home

- Jack Gantos

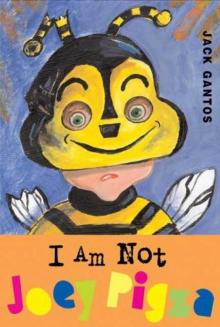

I Am Not Joey Pigza

I Am Not Joey Pigza Read online

For Anne and Mabel

Table of Contents

Title Page

1 - EVERYBODY LOVES A WINNER

2 - KNOCKOUT PUNCH

3 - HANDCUFFED HEARTS

4 - TO DINE FOR

5 - OFF THE GRID

6 - IN THE BAG

7 - FAST FOO

8 - GOT TO GIVE TO GET

9 - GRANNY’S COMET

10 - PAINT-BY-NUMBERS CHRISTMAS

11 - THE NOISE INSIDE

12 - BUZZED

13 - WHAT GOES AROUND

A NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR

GOFISH - QUESTIONS FOR THE AUTHOR

DEAD END IN NORVELT

READ ALL FOUR JOEY PIGZA BOOKS! AVAILABLE FROM SQUARE FISH

Copyright Page

1

EVERYBODY LOVES A WINNER

You know me. I always have to have something on my mind or something in my hands, otherwise my mind chases off in one direction and my hands go in another. This is how trouble starts for me, because if my mouth controls my mind and my hands control my body then I’m totally split in half and as my grandmother once said to me, “You are like a chicken with its head cut off.”

“I am not,” I argued right back, puffing out my chest. “My head is screwed on!”

“Not for long,” she snapped, and lunged at my neck with her bony fingers, but I was too fast and ran off.

Granny didn’t like to be wrong, and the next day she brought a live chicken home when Mom was at work and called me out to the backyard. “Watch this!” she said breathlessly as she flicked her cigarette toward St. Mary’s Cemetery, which bordered our backyard. She stepped on the chicken’s neck and pressed it to the ground with her bare foot as she raised a hatchet up into the air. “What you see next is just what I’m warning you about.”

Then she brought the hatchet down.

“No!” I yelled, and gave her a push from the rear. Suddenly there was blood everywhere and I thought she had chopped her foot off, but it was only the chicken’s head. Quickly, she set the headless chicken upright on the dirt and it took off running in circles with blood spurting from its neck until in a spastic moment it flew up and over our side fence and into the unfriendly neighbors’ yard and around the far corner of their house. We didn’t ever lay eyes on it again.

“See what I mean?” Granny ranted that evening when we smelled roast chicken coming from the neighbors’ house while we were eating cold cereal. “When it comes to your head, you either use it or lose it.”

That night I slept with my head under the pillow. I didn’t want to become someone’s dinner, but my sneaky Chihuahua-mix dog, Pablo, dragged that chicken head out of the trash and onto my bed and gnawed on it for his dinner, and when I woke in the morning and saw the pulpy bits of it all ripped apart I threw up, which made a gross thing grosser because he abandoned the chicken head and began to eat my throw-up, which made me throw up again and he wanted to eat that, too. Once, I asked the vet if Pablo could have a med patch like mine to make him less hyper, and the vet said his meds would be called “a cage.”

So anyway today I was walking home from school thinking about this Granny chicken business and wondering if I could make a headless chicken costume for Halloween next week, when I passed a box for a small Little Chef Boy refrigerator and it stopped me in my tracks. As strange as it sounds, refrigerator boxes really remind me of my grandmother because in the old days when my spring got wound too tight she was always threatening to put me in a refrigerator and give me a “Special Granny time-out”—which would have been an eternal time-out ‘cause everyone knows that if you stick a little kid in a refrigerator for too long then you just have to push the refrigerator over onto its side and it becomes a pretty handy coffin. Just lift the door open so the light pops on, and if it were me inside you’d find my stiff fingers folded neatly around an empty mayonnaise jar and a big creamy white mustache on my upper lip. But it didn’t get to this. Granny never could manage to shove me inside a refrigerator because my arms and legs are long and I was like a four-legged octopus gripping the outside edge as she pushed on the soft middle of me.

“I promise to let you out before you turn dark blue,” she’d grunt, huffing and puffing and trying to make a deal. But I knew better, even after she offered me money, because you can’t spend it when you are dead.

When I saw that box in some neighbor’s front yard trash pile I stood there for a minute thinking about Granny because she is the one who is dead and buried in St. Mary’s Cemetery now and I miss her. I didn’t mean to start thinking about what she went through—being cremated and her ashes poured into her special jar—but then I did start to imagine it and when I pictured her coffin all in flames and her hair on fire and all the awful thoughts you can have about a dead person you love, I just got really antsy and had to think of something else. I had to do something with my hands so I could put my racing mind to rest.

I glanced over my shoulder and made sure nobody was watching, then I hunkered down like a cartoon burglar does before he steals something and I grabbed the box by one of its loose flaps and began to drag it loudly down the street to my house. It sounded like I was dragging a really unhappy animal by the ear. I still wasn’t sure what I was going to do with it, but I just had a burning need for that box. I guess I missed my grandmother, and hauling a box around was a lot better than digging up her jar full of ashes for a graveside chat. I knew Mom would flip if I dragged a dirty box off the street in through the front door because of her “house beautiful” rules which just started a few months ago after a big truck pulled up and instantly we had all new furniture and wall-to-wall carpeting.

“Where’d that stuff come from?” I asked her because she was always saying we were flat broke whenever I wanted something new.

“Secret admirer” is all she said, and then she got that lost-in-love look on her face and I dropped the subject. I never like hearing about her boyfriends because I’m supposed to be her “big man” around the house.

So I dragged the box around to the back of the house and I guess that’s when my mind kicked in because the moment I dropped the box my hands stopped working and I got a big idea. It was so big it allowed me to have fun and do my homework at the same time. When we started studying geography and America’s borders this year my teacher, Mr. Turner, pointed to a pull-down map of Canada, and the moment he did I popped up and yelled out that I had been on a bus trip to Niagara Falls with my mom this summer and there was a museum full of the barrels that people used to float down the river and go over the falls in. “And some of those people died!” I shouted. “Died badly!” Before Mr. Turner could warn everyone not to try going over the falls themselves, I added, “And some of the people actually went over the falls with their pets!”

And then when he started speaking again I remembered another detail and shouted out, “And some of the pets died badly, too!”

Not one person in the class believed me. They never believed me, because during the Sensitivity Lesson on the first day of school when we were all practicing how to be really honest and kind to each other I was dumb enough to honestly announce that I actually made up more stuff than I really knew because my imagination was bigger than my brain. Since then nobody has believed a word I say, which is not very sensitive of them.

“But this time I’m telling the truth!” I insisted. “At the museum they showed a dog that had been squished on impact and looked like a furry pancake with a tail.” I turned left and right and tried my best to look twenty-eight kids in the eyes all at once which only made the center of my eyes vibrate. And while I was in the middle of a shouting match with everyone Mr. Turner stood up and asked us to chill out and then he looked at me and said, “Joey I want you to do some res

earch on this Niagara Falls subject and get back to us.”

Well, when he said “get back to us” I just instantly yelled out, “I’m the king of getting back to you on that!” And he said he knew this already and gave me a wink. I figured some other teachers had warned him that I was sometimes like a windup pirate’s parrot screeching Can I get back to you on that! Can I get back to you on that!, which used to make me laugh like crazy. I like Mr. Turner because he takes me less seriously than he has to, even though he once asked me if my mouth had a tiny mind all of its own.

I was thinking about all this as I dragged the box up to the top of the slide on my swing set. It was an old kind of slide with a metal surface and not the plastic kind, which is kid-friendly but also kid-boring. I mean, you need something solid and smooth like the metal kind if you are going to coat it with Wesson oil and put a cookie sheet or something on it and fly down. I was going to use the box to experiment with going over the falls. I knew the barrels that people had sat in were filled with some kind of cushioning material, so I raced into the house and yanked some fancy throw pillows off the new couch before Mom saw me. But Pablo and my new dog, Pablita, heard me, which was good because they followed me out back where they could be part of my research experiment.

I shoved one pillow right up into the front of the box and slipped one in on each side, and then I climbed down the ladder and pulled my arms out from my T-shirt holes so that the shirt just hung over my body from the neck down like a poncho. Then I scooped up the dogs and slipped them under my shirt so that their heads stuck out of the empty armholes and made me look like a three-headed freak boy. It was hard to climb the ladder this way so I used my teeth to grip the rungs as I hiked myself up. The metal rungs tasted like rust and dirt and reminded me of the taste of blood, which should have been a warning, but my mind was focused on other things. Once I got to the top I had trouble keeping my balance because the dogs were yapping and scratching up my belly with their jittery sharp nails, but I still managed to crawl into the box and kick out at the top of the ladder with my foot. The three of us went screaming down the falls for half a second before the box slowed down and didn’t even drop off the bottom lip of the slide. The whole operation was a Niagara-size dud. And then while my hands were tied up with the dogs my brain really got going, so I imagined that getting the box up on the porch roof might be good because it slants down at an angle and we could really do a daredevil job from there. So I wiggled around until I got us all out and then I got my old plastic wading pool from in the weeds by the back fence. There was rainwater in it and some droopy blow-up toys from summer and I dragged the pool below the porch roof where I thought we would splash down.

It was a great plan.

To make it work I first stuck my head in the back door and listened. I could hear the high-pitched whine and grind of Mom’s electric hobby sander. Ever since she had perfected her nail-sculpting skills she’d been telling me that big things were about to happen—like how she might leave the Beauty and the Beast Hair Salon and go into business for herself.

“Mom!” I shouted when she paused the machine. “Can I have a snack?”

“You have to get it yourself,” she shouted from upstairs. “I’m styling my toenails.”

Perfect, I thought. I grabbed the box and dropped the dogs inside it and then tugged and kicked it across the carpet. Then as quietly as I could I pulled it up the staircase one thump at a time until I had it in the room we didn’t often enter because Mom said it was haunted by the smelly “Pigzas of the Past.” I knew she meant it was where she had stored some of my dad’s junk and his moldy old clothes from when he ran off right before I was born. The room did smell, but I dragged the box across the rough floor and tugged the old wooden window frame up and open and took a deep breath. I looked across the slope of the porch roof. It didn’t look steep enough, but then I thought I could put the box in the window with the open end facing me. Then I’d hold a dog in each arm and run from across the far side of the room and dive into the open box which would definitely shoot us across the roof and down.

Then the front doorbell rang. It was the singsongy ding-dong type.

“Can you see who that is?” Mom called out from behind the closed door of her bedroom.

“Do I have to right now?” I yelled back. “It’s just some ding-dong.”

“Please just do what I ask you to do when I ask you to do it,” she yelled back. Then I heard her hair dryer start up and I knew she was now trying to dry the polish on her sculpted toenails as fast as she could. She must have been expecting someone romantic.

“Stay where you are,” I said to the dogs, but they didn’t and followed me down the stairs then came to a screeching halt right behind my screeching halt as I opened the door.

And there in front of me was my no-good squinty-eyed bad dad, Carter Pigza, who I thought was gone for good last year after he ran off when Mom wouldn’t have anything to do with him. I tried to slam the door but he wedged a shiny brown shoe across the threshold. The shoe looked like a gigantic cockroach so I stomped on it. But the bug didn’t budge.

“Go away!” I shouted, and stomped on it again.

My dad pushed on the door just enough for his tanned, leathery face to fit through the gap. I pushed back. I wish I could have slammed the door and pinched his head off, but he was too strong for me.

“I know what you are thinking, Joey, but you are wrong,” he said, now thrusting his hand in and tapping on the tip of my nose. I jumped back and the door sprang open all the way but he stayed put on the threshold and smiled from one teacup-shaped ear to the other.

“You think I’m your old good-for-nothing dad, Carter Pigza, coming back to cause trouble like before,” he started like some wise old owl who could read my mind. “But I’m not Carter Pigza anymore. Nope. You can forget about that Carter guy. He’s history!” He puffed himself up. “I’m a new person now. It’s like I died and was reincarnated. It’s like you’ve never seen me before. Like you don’t know a thing about me—not even my real name. It’s like I’m a mystery man to you.”

I don’t know how he did it but he ran his hand over his weathered face and instantly his deep wrinkles flattened out as if someone had drawn his face on an Etch A Sketch and then gave it a little shake. He looked soft and slightly out of focus.

“I’m a mysssstery man,” he hissed, then ran his hand back across his face, which spookily refocused his features.

I stared out at him suspiciously, like I did when the confused person from the retirement home showed up in a trick-or-treat costume in July. Now my dad was dressed differently too—nicer than I’d ever seen him before. Normally he was wearing a greasy work uniform or his scuffed-up old motorcycle leathers, but now he had a suit on with a white shirt and red tie. I glanced down at his shoe, half expecting to see a long shoestring that was a lit fuse, as if this fake Carter Pigza would suddenly blow himself away and the real nutty Carter Pigza would be left standing in front of me snapping at the air like a bad dog on a chain.

“You are scaring me!” I said. “You shouldn’t be here! Mom hates you and this is weird.”

“Not weird,” he countered, raising one finger. “Wonderful! The slate’s been wiped clean for me. One day I just woke up and said goodbye to the ugly past and hello to the big bright future. Now I’m a brand-new man with a brand-new plan. I’m Mister Charles Heinz, the man I’ve always wanted to be.”

He was so creepy.

I took a step backward because I was thinking that if he lunged for me I wanted to have a head start.

“And do you know who you are?” he challenged, staring directly into my eyes.

“Yeah,” I said calmly. “I’m Joey.”

“Not good enough!” he shot back. “You have to dig deeper than just your name to know who you are.”

“How deep?”

He thumped himself on his chest with his fist. “To the core!” he said, wide-eyed. “Deep to the core.” Suddenly he reached into his pants p

ocket. I don’t know why but I thought he was going to pull out an apple core and give me a demonstration.

I inched back even farther.

“I have a gift for you,” he said in a surprisingly different voice. It was a soft, warm voice—the voice I always wished he’d have. Then in a slow and teasing way he tugged out a crisp hundred-dollar bill. “Here, it’s all yours,” he said, holding it by one corner as a little breeze waved it back and forth.

I leaned way forward until it was in front of my nose then reached up and snapped it out of his fingers. I had never touched a hundred-dollar bill before. I held it up to the light and narrowed my eyes as I searched for the watermark.

“Is it fake?” I asked, turning it over.

“Heck no!” he said, and chuckled at the thought. “And there is plenty more where that comes from.” He plucked another hundred from his pocket as easily as pulling a tissue from a box and in one smooth motion he ran it under his nose and gave it a deep, satisfied sniff.

Pablo shuffled forward and gave him a curious look, then sniffed him as if he’d never seen him before.

“Don’t you remember this man, Pablo?” I asked, lowering the hundred-dollar bill. “He’s the creepy guy who dognapped you last year so he could get Mom’s attention.”

Pablo just sneezed and drifted toward the living room with Pablita to watch Spanish soap operas on TV Mom had been trying to learn Spanish because Lancaster has a lot of Spanish-speaking people now and one came in to get her hair cut and Mom guessed at what she was saying and instead of “trimming the ends” she did something that made her hair look like a feather duster and the woman was so upset Mom vowed to learn Spanish. This made me think of her, so I yelled out, “Mom! I need you. ¡Rápido!”

I was learning Spanish, too.

“May I come in?” my dad asked calmly.

May I?

He has changed, I thought. He never sounded so polite in all his life. Suddenly I recalled his new name. “Charles Heinz?” I asked. “Where’d you get that?”

Jack Adrift

Jack Adrift Jack's New Power

Jack's New Power Jack on the Tracks

Jack on the Tracks I Am Not Joey Pigza

I Am Not Joey Pigza The Bloody Souvenir

The Bloody Souvenir Joey Pigza Loses Control

Joey Pigza Loses Control Heads or Tails

Heads or Tails Hole in My Life

Hole in My Life What Would Joey Do?

What Would Joey Do? The Trouble in Me

The Trouble in Me Joey Pigza Swallowed the Key

Joey Pigza Swallowed the Key From Norvelt to Nowhere (Norvelt Series)

From Norvelt to Nowhere (Norvelt Series) The Key That Swallowed Joey Pigza

The Key That Swallowed Joey Pigza Jack's Black Book

Jack's Black Book Dead End in Norvelt

Dead End in Norvelt