- Home

- Jack Gantos

Jack Adrift Page 2

Jack Adrift Read online

Page 2

Dad took off his shoes and socks, hopped out, and sloshed his way around the car. He picked Mom up like a new bride and carried her up the few steps. She reached out and turned the doorknob. It was unlocked and they stepped right in. A moment later the lights inside began to come on. I peeled off my shoes and socks and Pete crawled onto my back. “Puke on my head and I’ll drop you,” I said, as I carried him through the water.

“Drop me and I’ll need mouth-to-mouth resuscitation,” he gurgled.

That was a disgusting thought.

Betsy sat in the car by herself, pouting. I knew she was wishing for the worst and had her fingers crossed that things inside the house would be so bad we’d all just run screaming back to the car, and Dad would drive down the road and over the bridge and all the way back to our hometown, where Betsy had a million great friends. I knew how she felt. I was leaving my friends behind, too. But since she was three years older than me she knew hers longer, and because of that I figured she’d miss them more.

But the little house wasn’t so bad. The Navy had filled it with new furniture and carpets. As Mom said, “It’s not fancy, but its good family furniture.” There were clean pillows and linens folded on the fresh mattresses, and the bathroom was spotless. The kitchen was small, but everything in it was spick-and-span. There was a new couch with a matching coffee table and lamps.

Pete threw himself on the couch like a dead dog lying on its back, with its legs straight up in the air.

“If you have to be sick, do it in the bathroom,” Mom insisted.

“There’s no TV,” he whined. “I’ll never get better.”

“You don’t need one,” Dad said. “TV is only for people who are stuck out in the sticks. We are in Cape Hatteras! There are millions of things to do here.”

I looked out the front window to see if I could find some of the millions of things to do. Across the street was a Gulf gas station. The sun had almost faded and the round orange Gulf sign shined orangely onto my face. “It looks like a giant orange lollipop,” I said to Betsy, who had finally given up and come into the house to haunt us.

“No,” she said sharply, “it’s a giant sucker they put up just in your honor.”

“You know,” I said, trying to sound like Mom and keep my spirits up, “this moving is hard enough without you being nasty on top of it all.”

Betsy stepped back and put her hands on her hips. “I’ve been thinking about what Dad said, and you should worry about making friends,” she said directly. “You are a boy. And boys don’t make friends, just enemies. Girls make friends like this,” she said, snapping her fingers. “Boys just size each other up like hungry wolves fighting over a hunk of red meat. And believe me,” she said, poking me in my soft belly, “you’ll make a nice meal for someone.”

Just then Mom walked up to us. “That Gulf sign makes us look like we have jaundice,” she said, holding me by the chin and looking into my eyes. “Even your eyeballs are orange.” She pulled down the shade, then looked at Betsy and put her arm around her shoulders. “Come on,” she said warmly, “help me make up the beds and get this place organized.”

“Okay,” Betsy said. She sounded tired of being miserable.

“Jack! Pete!” Dad called from the front door. “Come help me unload the trunk.”

“Yes, sir!” I hollered back, and saluted in his direction.

“Yes, sir!” Pete said, and crawled off the couch. He was tired of being miserable, too.

After Mom got the kitchen boxes unpacked, we ate dinner from the cooler full of leftover food we had packed for the trip. As I looked around the table, it seemed that everyone was doing much better. Betsy was happy because she had gotten her own little room. As usual, I had to share with Pete. Mom was happy because the house was clean and easy to keep that way. And Dad looked ready to hit the sack and get charged up for his new ambitious life.

After I took a shower in something like a tin phone booth, I said good night to everyone and crawled between my sheets, which smelled like Cream of Wheat. I was exhausted, but before I fell asleep I still wondered what the kids at school might want to hear about me. I knew Mom was right, that I should just tell the simple truth: I was from a small farm town full of nice people with enough oddballs thrown in to make the place interesting. But I was more attracted to Dad’s advice. It just seemed much more fun to make up who I was, to invent myself so everyone would think I was interesting. And suddenly it struck me that maybe Dad said to tell people what they want to hear because he knew life was easier that way, that if you agreed with everyone they wouldn’t say mean things about you, or pick on you. I wanted to get up and ask him if that’s what he meant by telling people what they wanted to hear, but I knew he was already asleep, and wouldn’t want to hear from me. Soon, I didn’t want to hear from myself anymore and drifted into sleep.

In the morning I opened my eyes and looked directly out my window. There was a kid staring at me. He was standing up to his knees in the little swamp between our two trailer homes. His hair formed a perfect V down the middle of his forehead, kind of like the pointy end of a can opener or, as Dad would say, a church key. When he saw me staring back at him he waved.

“Where are you from-from-from?” he asked, sloshing through the pea-green water.

“New York City,” I replied, lying before I could stop myself. I guess I was more Dad than Mom.

“Oh,” he said, impressed. “We’re from a town so small-small-small I’m sure you’ve never heard of it. My dad’s a carpenter for the Seabees.”

“My dad’s an admiral,” I said, lying through my teeth. I couldn’t seem to help myself, then I lied some more. “But he’s wearing a disguise so he can catch all the unambitious sailors who just goof off all day.”

The kid looked back at me with his head bobbing up and down like a dog toy in the back window of a car. “Wow, I always wanted to meet an admiral’s kid,” he said. “Do you ever get to steer the ships?”

“Steer them, and fire off the big guns,” I boasted.

His jaw dropped. “What’s your-your-your name?” he asked, repeating his words like the excited goose in Charlotte’s Web.

“Jackson,” I said, “like President Jackson.” I knew I was off to a bad start. “What’s yours?”

“Julian,” he replied, splashing forward and up onto dry ground until he could stick his wet hand through my window.

I shook it. “Nice to meet you,” I said. At least that wasn’t a lie.

Respect Detective

The water receded, the sky cleared, school began, and I was in luck. My new teacher was young and enthusiastic and full of great creative ideas. Each morning she dashed through the classroom door with her long wet hair smelling like a bouquet of flowers and her arms filled with papers and supplies for projects. “Sorry, I just got out of the shower,” she’d say breathlessly as she dumped everything on her desk then flicked the blond strands of hair out of her blue eyes. She was smart. She was beautiful. I loved her instantly.

My third-grade teacher back in Pennsylvania was old and worn-out. It had been her last year before retirement and instead of treating us like students, she turned us into her own private staff of servants. When she pulled up in the parking lot, we hustled out to her car and carried in all her book bags, her purse, her special low-salt lunch, her favorite pillow, and her embroidery kit. Then we gently supported her shaky arms as we took baby steps all the way inside to her desk. Her hair was as dried out as steel wool. She was rusting away and spent no time thinking about how to make education fun. Instead, she always gave us plain old workbook assignments after settling down in her chair for the day. She had a large alarm clock ticking loudly on her desk, and it regularly went off with an ear-drilling ring whenever she needed to take one of her many medications. Because of her age and ailments she was excused from cafeteria duty, and after lunch we would creep back into the classroom to find her slumped forward on her desk napping with her head on an unfinished embroidered pillow. We’d

pull the curtains and turn off the lights and she’d sleep until the alarm clock rang. She’d wake up confused and stare out at us with eyeballs as murky as peeled grapes. She seemed not to know where she was. It was like having class in a very sad retirement home. For extra credit we could rub her feet. She had corns and bunions that were as big as the knobs on an old radio. She gave us a tool that looked something like a cheese grater and we scratched it back and forth over the knobs and shaved them down a bit like you would a radish. At the end of the year we chipped in and bought her an automatic foot massager.

But my new teacher was like a college girl. I stared up at her dreamily all day long and did everything she asked. And when she needed a volunteer I alertly raised my hand before I even knew what she required. If she had said, “I need a body to dissect,” I would have thrown myself across her desk with a scalpel between my teeth. I dreamed she would carve her initials into my shoulder. If she needed a kidney I’d donate one of mine. In a very rare operation we could switch beating hearts. She called on me a lot, and I was certain she thought I was the special one in class, even though my mind drifted a bit.

After about a week Miss Noelle stood thoughtfully in front of us and slowly rolled up her shirtsleeves. She looked us up and down one by one, as if we were slabs of stone she was about to carve. “I have a great desire to get to know you all better,” she announced. “So I’ve come up with a fun writing assignment. First, I want each of you to write the story of your life exactly as it is. No exaggerations. No stretching the truth. Then, I want you to write a second biography which is the story of your life as you wish it to be.”

I loved the idea. She was so inventive.

“I need a volunteer,” she called out.

Reflexively my hand shot up, and without hesitation she called on me. “Pass out one of these composition books to every student,” she instructed. “They’ll be your ungraded, write-whatever-you-want journals. Anything goes! Shoot for the moon!”

I leaped out of my seat and grabbed a stack of black-and-white composition books off her desk. I passed them out with my head held high as if I were a priest delivering communion.

Soon, we all picked up our pens and bent our heads and got busy. It didn’t take long to write the basics of my real life—where I was born, the names of my family members, and the few exciting things that had happened to me—all written in detail just as honestly as my mom would have told it.

But when it came to writing about my life as I wished it would be, I found it a bit more difficult because I could hear my dad’s voice in the back of my head saying, “Tell her what she wants to hear.” I just didn’t know yet if she wanted to hear that I was madly in love with her.

I was sucking on the tip of my pen and turning my tongue blue when over the loudspeaker the secretary’s voice burst in. “Excuse me, Miss Noelle. Could you send Jack Henry down to the principal’s office?”

I glanced over at Miss Noelle with an alarmed look on my face.

She winked at me, then nodded toward the classroom door. “Chin up,” she said.

But as I meandered down to the principal’s office I was nervous. The office secretary spotted the panicky look on my face. “Don’t worry,” she assured me. “Mrs. Nivlash won’t bite. She’s simply lovely.” I had been bitten by a lot of lovely dogs that were not supposed to bite. As the secretary opened the principal’s office door she announced my name and with her hip nudged me forward.

Mrs. Nivlash was wearing a bright yellow suit that my mom would describe as a businesswoman’s mannish suit. She had been out in the sun a lot. She looked like well-dressed beef jerky. An orange scarf twisted around her neck gave her shiny face a devilish glow. I squinted at her as if looking into a ring of fire.

“I’ve been meaning to take this opportunity to welcome you to our school,” she said politely, dipping a tea bag into a cup of steaming water. She stood and leaned across her desk to shake. Her hand was large and her fingers wrapped around my palm and wrist like bony cables. “Take a seat,” she said, releasing her grip. I tipped back into a chair. “I’ve been thinking that your arrival at First Flight Elementary is a great opportunity for all of us, because we have a problem here and I think a new boy like you can help.” She fished the tea bag out of the cup and squeezed it dry. “Let me explain. Last year there was a horrendously bad gum-chewing epidemic going on around campus. Just awful. Gum was stuck everywhere, to everything. Over the summer we had to pay out a lot of money to have the gum professionally removed. And this year, I don’t want it to get started again. So here’s what I plan to do, and here is where you fit in. I’m going to make a new school service position—we have a head of safety patrol, and a head of school spirit, and a head of academic excellence. And now I’m going to give you the title of Respect Detective. You will be the head of school respect. What do you think of that?”

With her little finger she dabbed at the caked red lipstick in the corners of her mouth, then paused. I wasn’t sure what she wanted from me. I tried to look into her eyes for a clue, but when I did mine slid away from hers as if our eyes were opposing magnets. I glanced around her office to see if I could gather any hints. Her bookshelves were lined with detective novels. She had a target-shooting trophy in the shape of an enormous golden pistol. Her letter opener looked like a bayonet. There was a framed photograph of her dressed as a police officer. All I could assume was that she had had a previous career in law enforcement before deciding to run a school. Perhaps, she figured, if she could set straight the up-and-coming criminals when they were young, it was better than catching them after they had committed some awful crimes as adults. That made sense to me.

Mrs. Nivlash cleared her throat. “Well?” she asked.

Her hands gripped and twisted and ungripped each other like competing wrestlers. I could tell she was a person who didn’t like to be disappointed. In this case I knew it was better to follow Dad’s rule and tell her exactly what she wanted to hear.

“I’m very excited,” I said, as respectfully as possible. “Very.”

“Good,” she said warmly, then stood up and closed her door. When she sat down again she smiled gleefully and leaned toward me. “Now here’s the plan. I’m going to allow gum chewing for a one-week trial period. If they’re good, I’ll promise to extend it for another week but, believe me, it won’t get that far. Now, you may think it is mighty strange that a principal would allow gum chewing, but there is a method to my madness. I’m guessing that our little gum-sticking criminal will not resist the first opportunity to stick his or her gum where it does not belong, and this is where you come in. As the newly created Respect Detective, you will be my eyes and ears among the students. You will identify the gum sticker, and you will turn him in to me. In return,” she said slowly, pointing her finger directly into my face, “I will take very good care of you. Unless you do something bad yourself, I will see to it that nobody troubles you. Any questions?”

“Well, what if nobody sticks gum on things?”

She threw her head back and laughed so hard she snorted. “Impossible!” she said when she had settled down. “We’re dealing with kids. Give them any little chance to screw things up and they will.”

She unlocked a file-cabinet drawer beneath her desk, opened it, and removed a manila folder clearly marked SECRET in red ink. She flipped it open and set aside a Respect Detective identification card. “Here,” she said after writing my name on it. “I had this made up for your new position.”

“Should I pin it on my shirt?” I asked.

“Heavens no,” she said sharply. “It’s just between us. Keep it hidden. Don’t let anyone see it. Not even the teachers. They chew gum, too.”

“Okay,” I said, and shoved it down into my back pocket.

“Now get going,” she instructed. “I’ll make the gum-chewing announcement today. Then I want you to keep your eyes open for the perpetrator.”

“What will you do when you catch him?” I asked.

�

�I’ll make him the new Respect Detective,” she said, smiling broadly. “I think it will be rehabilitative for each perpetrator to have to catch the next violator.”

How clever, I thought. No wonder she was the principal.

When I left her office I was so relieved I wasn’t in trouble that I didn’t think a lot about what it meant to be her Respect Detective. I shrugged it off as one of those weird yearbook categories like Dress-Code Coordinator or Manners Monitor. I was mostly thinking about Miss Noelle and getting back to the class so I could dream about our perfect life together and occasionally do a little work on the writing assignment.

By recess I still hadn’t written anything about what I wished for, because I wasn’t quite sure Miss Noelle and I were thinking alike. I sat in the shade under the sliding board and simply wished that somehow we lived together, that she was my teacher, my mom, my big sister, and my girlfriend rolled into one. I wished we lived on a yacht. I wished we were CIA spies. I wished we were on game shows together and won sensational vacation trips and stacks of cash. All my wishing was confusing and made me blush when just thinking about nothing more than holding her hand. So I tried not to think about it, and I certainly couldn’t write about it, because what I had in mind was so disrespectful I’d have to turn myself in to Mrs. Nivlash.

Suddenly the gym teacher blew his chrome whistle. Our heads snapped around toward him. “Everyone off the playground and back to your classrooms!” he instructed, waving toward the side entrance. “Now!” he barked, as if a cloud of enraged killer bees were swarming toward us. We froze for a second, then followed his orders. He was young and energetic and wore tight white T-shirts to show off his muscles. I didn’t like him because he was always poking his sunburned nose into our classroom and asking Miss Noelle if she needed help disciplining any of the boys or had time after school for some extra tutoring. Some kid told me he had been a pro football player who had received a terrible career-ending injury. Whatever the injury was, I couldn’t locate it. Perhaps it was deep inside his head. As my dad would say, “Too many games without a helmet.”

Jack Adrift

Jack Adrift Jack's New Power

Jack's New Power Jack on the Tracks

Jack on the Tracks I Am Not Joey Pigza

I Am Not Joey Pigza The Bloody Souvenir

The Bloody Souvenir Joey Pigza Loses Control

Joey Pigza Loses Control Heads or Tails

Heads or Tails Hole in My Life

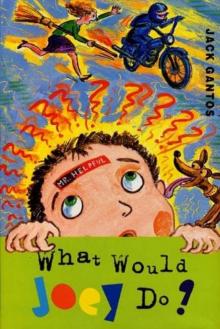

Hole in My Life What Would Joey Do?

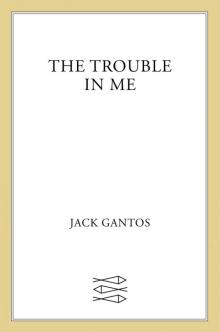

What Would Joey Do? The Trouble in Me

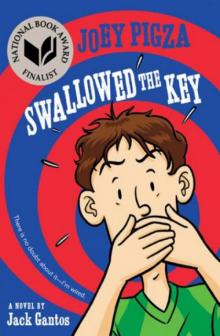

The Trouble in Me Joey Pigza Swallowed the Key

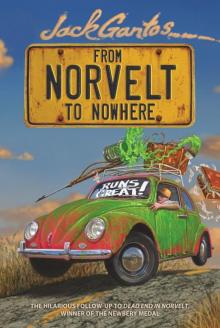

Joey Pigza Swallowed the Key From Norvelt to Nowhere (Norvelt Series)

From Norvelt to Nowhere (Norvelt Series) The Key That Swallowed Joey Pigza

The Key That Swallowed Joey Pigza Jack's Black Book

Jack's Black Book Dead End in Norvelt

Dead End in Norvelt